Creating ‘Good’ Digital Public Infrastructure

Looking beyond the ‘tech’ aspects of digital public infrastructure to how it interacts with users as individuals, as collectives, and in societies

Kriti Mittal, Varad Pande & Aishwarya Viswanathan | 30 October 2022

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed that despite the vast difference in our geographical, cultural, social, and political contexts, one thing that countries all over the world urgently need is digital public infrastructure (DPI). DPI comprises foundational population-scale technology systems on which the digital economy operates, such as identity systems, payment systems, data exchanges, and social registries. Some countries, such as India, were able to leverage existing DPI to provide targeted social protection assistance to their citizens amidst the pandemic; on recognising the benefits of ‘digital-delivery’, others such as Togo and Sri Lanka undertook efforts to rapidly build their own. The demand for DPI among countries has grown significantly since then, with the World Bank’s Identification for Development initiative alone currently supporting 49 countries to implement digital IDs.

Conservative estimates suggest that Estonia’s X-Road—an open-source government data exchange system that facilitates the provision of over 99 percent of all government services digitally—saves Estonians an estimated 820 years of working time every year and approximately 2 percent of GDP.

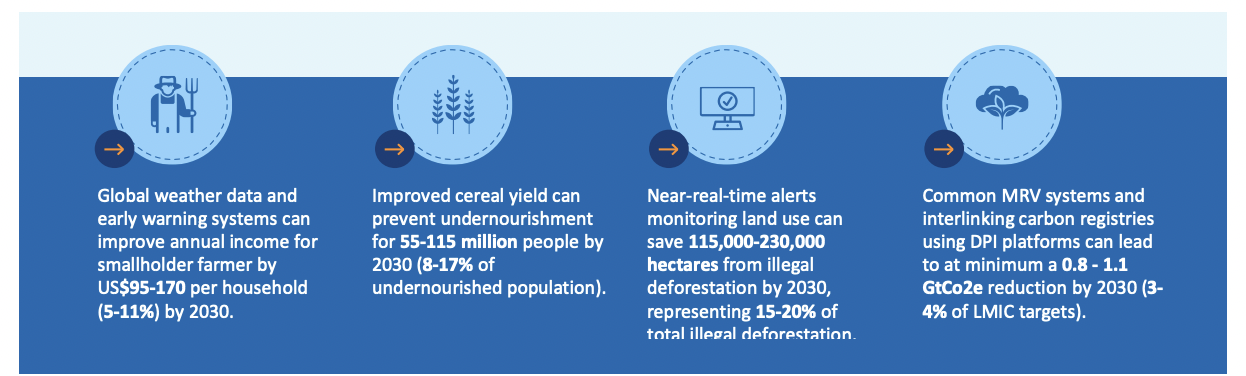

Today, DPI is increasingly being built using open-source and modular technologies that enable ‘interoperability’, which facilitates the exchange of information between different arms of the public and private sector, thereby, vastly improving the speed and scale of service delivery. This represents a paradigm shift from older end-to-end siloed systems, wherein governments provided end-to-end services through monolithic tech systems, to building minimal digital infrastructure that allows multiple actors to build solutions on top. DPI designed in this way can mean significant time and cost savings. For instance, conservative estimates suggest that Estonia’s X-Road—an open-source government data exchange system that facilitates the provision of over 99 percent of all government services digitally—saves Estonians an estimated 820 years of working time every year and approximately 2 percent of GDP. Another DPI success story is India’s Unified Payments Interface (UPI), which facilitates the largest number of daily transactions of any tech platform in the world, and is estimated to have resulted in savings of US $12.6 billion in 2021. Moreover, since its launch in 2017, India has been improving financial inclusion at a compound annual growth rate of over 5 percent, a significant expansion of India’s formal financial system.

‘Good’ DPI is More than Just the Tech

Given such unprecedented population-scale impact, there is now a growing consensus around the necessity of DPI. However, there is much debate about what constitutes ‘good DPI’. As countries embark on the journey of building, maintaining, and scaling their DPI, it is imperative to understand that the technology, no matter how powerful and essential, does not exist in isolation and cannot solve all problems by itself. To maximise the benefits of DPI for the provision of citizen-centric services, and minimise risks and potential harms, the ‘non-tech’ layers of institutions, legal and regulatory frameworks, and communities are equally, if not more, important than robust technology solutions.

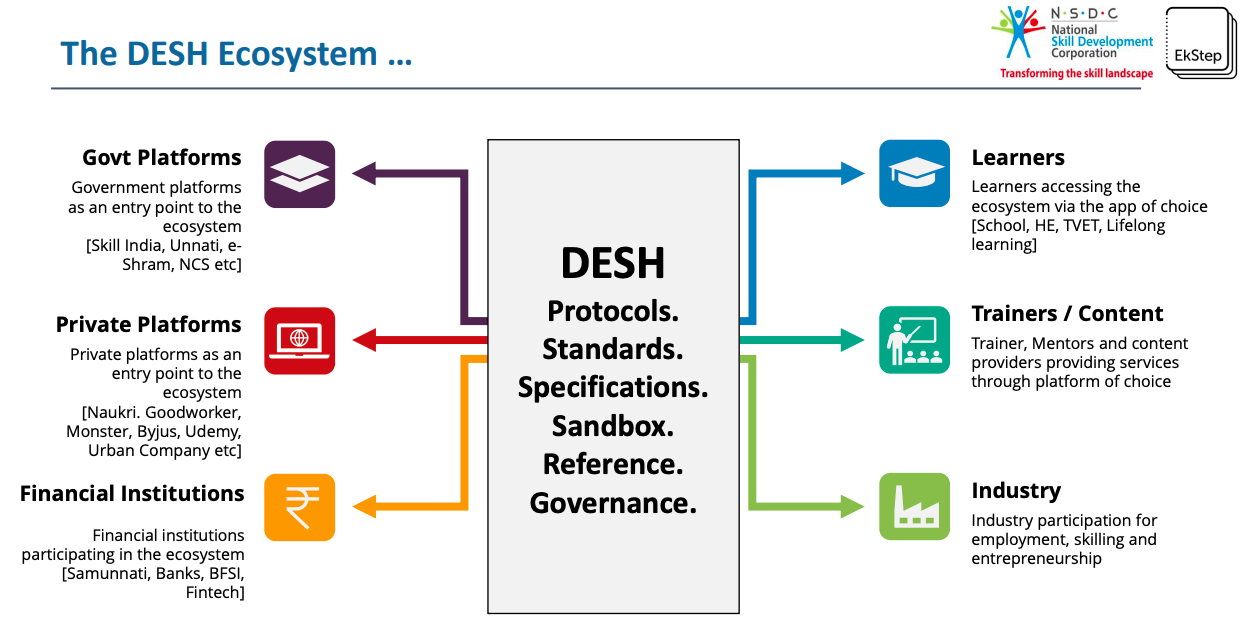

In this regard, the ‘open digital ecosystems’ (ODE) approach offers a useful framework and set of guiding principles, with a strong emphasis on strengthening DPI through citizen-centric design and safeguards, sustained community engagement, institutional capacity building, and robust governance.

Building trust in the context of DPI has many dimensions—from data security and privacy to institutional accountability and grievance redressal, to proactive communication and change management.

To design ‘good’ DPI, countries can build on the ODE approach and focus on getting three key ‘non-tech’ elements right: Trust, access, collaboration.

- Building trust in the ecosystem to drive DPI adoption

The potential of DPI to generate new economic and societal value largely depends on the extent of end-user adoption, which, in turn, depends on how much citizens trust the new technology. Building trust in the context of DPI has many dimensions—from data security and privacy to institutional accountability and grievance redressal, to proactive communication and change management.

In an increasingly digitised society, data privacy and security are among the biggest risks for users if DPI is not designed with adequate safeguards. Safeguards can be built in both the tech and non-tech layers. Firstly, they can be incorporated into the design of the technology itself as a ‘default setting’ to protect all citizens, including those who may not be equipped to make active choices to protect their personal data. Secondly, safeguards can be put in place through robust governance (data protection laws and accountable institutions).

‘Security-by-design’ and ‘privacy-by-design’ principles, which include both technological and policy choices, can be incorporated at all stages of the development of the DPI. Security-by-design principles, to ensure secure processing and sharing of data, include access control, encryption, anonymisation, and the like. Privacy-by-design principles include ensuring data is collected for a specific and limited purpose, designing mechanisms for informed consent for data sharing that are in adherence with relevant data protection laws, and defining usage and obligations around the processing of data.

‘Security-by-design’ and ‘privacy-by-design’ principles, which include both technological and policy choices, can be incorporated at all stages of the development of the DPI.

Additionally, countries can learn from ongoing research on behavioural science approaches to data privacy that are experimenting with innovative mechanisms, such as behavioural nudges and simplified privacy ratings, which aim to reduce the ‘burden’ of making privacy-conscious choices from the end users. Supporting such ‘responsible tech’ choices can play a key role in ensuring the security and privacy of citizens’ data and, thereby, building transparency and trust in the digital infrastructure.

The other key dimension of trust is the accountability of the ‘institutional home’ of the DPI. For example, in India, the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) is the institutional home of the Aadhaar system. Similarly, the National Health Authority is the institutional home of the digital health infrastructure. Ensuring accountability of these institutions includes conducting frequent public consultations, having responsive grievance redressal, establishing the right legal and institutional structure in line with the objectives of the DPI, and guaranteeing transparency in reporting and disclosing audits. The risk of diffusion of accountability because of multiple actors being involved in digitally-mediated service delivery between the state and the citizen must be proactively addressed.

Lastly, DPI implementation results in significant changes in the roles of last-mile government functionaries, as well as the processes through which citizens interface with the state. Managing these changes sensitively, developing mass awareness campaigns and innovative mechanisms for government-to-citizen and citizen-to-government communications will be crucial for enhancing users’ experience, and a sense of connectedness and co-ownership of the DPI.

- Working towards universal digital access and inclusion

Digital accessibility—access to digital connectivity as well as digital literacy—is fundamental to the adoption of DPI. It is also critical, especially for low- and middle-income countries starting their DPI journeys, to ensure that digitisation does not deepen existing regional and socioeconomic divides.

According to the International Telecommunications Union, the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated access to the internet, with the number of users increasing from 4.1 billion in 2019 to 4.9 billion in 2021. However, access is not uniformly distributed, with stark urban-rural and gender divides persisting. In India, for instance, 2021 National Health and Family Survey data also shows only 24.6 percent of rural women have ever accessed the internet, as against 72.5 percent of urban men.

DPI implementation results in significant changes in the roles of last-mile government functionaries, as well as the processes through which citizens interface with the state.

Apart from access, limited digital literacy also impedes the meaningful adoption of DPI. Moreover, limited digital literacy or awareness also raises the risk of exposure to harmful online content, which can further disempower users and disincentivise adoption.

Measures must be taken to bridge these digital divides for countries to implement DPI without exacerbating existing structural inequalities. Multimodal access (feature phone, smartphone, computer) must be prioritised to accommodate for varying levels of digital access that might exist between different social groups. For instance, to drive the adoption of digital payments in India, the National Payments Corporation of India launched the UPI123Pay Service to allow feature phones without an internet connection to use UPI.

Field studies have found that even when digital services are accessible, trusted intermediaries or community anchors play a critical role in enabling adoption. Therefore, such a ‘phygital’ approach should be factored into the DPI vision. These intermediaries encompass a vast range of individuals and institutions, from local NGOs and community-based organisations to local politicians and trusted community leaders. By augmenting online touchpoints and processes with a human point of contact that often functions as the ‘last mile of service delivery’, omnichannel access can ensure underserved communities are able to access digitally-enabled service delivery.

Civic-tech organisations can also play an enabling role in facilitating last-mile inclusion by developing contextualised solutions, such as Gramvaani’s interactive voice response system for rural areas with limited connectivity, and Haqdarshaq’s ‘assisted-tech’ model where community-based field agents support citizens in accessing government programmes.

- Encouraging collaboration through open technologies

The ability to collaboratively build solutions on top of core technology infrastructure or to reuse and repurpose digital building blocks to create new solutions makes the current approach to building DPI unique and different from past approaches. This opens the possibility for individuals, startups, non-profits, and others to contribute to population-scale digital solutions. Open-source software and building collaborative communities are the two key elements to making this happen.

The adaptability of open technologies is also useful in creating customised solutions tailored to local contexts.

DPI set up in areas critical to the functioning of an economy must be able to accommodate any unexpected increase in demand in the number of transactions or users, and also be able to respond to the evolving needs of a large and diverse set of users. Promoting and mainstreaming the use of open technologies—such as open-source software, and application programming interfaces and protocols, where anyone is free to access, use and share code—can be useful as they encourage collaboration and distribute the ability to solve population-scale challenges.

The technological and legal features of open technologies help governments avoid vendor lock-ins and, consequently, lower the costs of switching between vendors of proprietary software. The adaptability of open technologies is also useful in creating customised solutions tailored to local contexts. In other words, open technologies are a key enabler of citizen-centric innovation.

Such open innovation can also lead to unlocking significant value for countries. A 2021 European Commission study found that an 10-percent annual increase in open source software contributions would boost Europe’s GDP by an additional 0.4 percent to 0.6 percent, while also creating more than 600 additional tech startups in the bloc.

While open technologies create the possibility for the wider community of open-source developers, startups, and civil society organisations to participate in the development of digital solutions and services, it is also important to create concrete avenues for the community to recognise this opportunity and have incentives to participate. Many countries adopting this approach focus on creating enabling environments rather than building end-to-end solutions by introducing mechanisms such as sandbox testing, incentive-based innovation challenges/hackathons, incubation centres, and other test beds that provide avenues for meaningful participation. For instance, Singapore’s digital transformation agency, GovTech Singapore, hosts a portal where the community can contribute towards testing and suggesting improvements to GovTech applications. Similarly, India’s DPI for healthcare, the Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission (ABDM), has outlined sandbox testing guidelines, which will allow innovators to test their products or services in a controlled environment. As of June 2022, 867 health service applications were tested in the ABDM sandbox, and 40 applications have been successfully integrated.

The Way Forward

The choices made by countries in the current era of building foundational DPI will have far-reaching consequences for future generations. From the point of view of long-term sustainability and equity, the most critical set of choices may be those pertaining to financing DPI and building the right kind of teams to manage DPI, with implications for trust, access, and collaboration.

Many countries adopting this approach focus on creating enabling environments rather than building end-to-end solutions by introducing mechanisms such as sandbox testing, incentive-based innovation challenges/hackathons, incubation centres, and other test beds that provide avenues for meaningful participation.

Setting up digital infrastructure requires specialised expertise in technology and other fields like data analytics, design thinking, and social sciences. Therefore, institutions set up to build digital infrastructure must have systems for encouraging collaboration across domains. Developing in-house capacity and procuring top-quality external partners to build and maintain DPI is one of the most common problems that governments worldwide are grappling with and trying to solve in different ways. For instance, UIDAI pioneered a unique talent strategy where it enlists the services of experts from academia and industry from diverse backgrounds to work with the organisation. It lays down the recruitment guidelines for professionals, volunteers, and sabbatical/secondment officers, and details the manner of engagement, selection criteria and the code of conduct. In the US, the Barrack Obama administration set up a ‘presidential innovation fellows’ programme, which evolved into a permanent technology team, to bring top talent into the US digital service.

Finally, developing a long-term financing model will be critical in ensuring the sustainability of DPI. In this regard, public resources are preferable for the development and maintenance of the ‘core infrastructure’ at the national level as this infrastructure must remain accountable to the wider population due to its pivotal role in enabling public service delivery. Private or philanthropic capital (typically with a higher capacity for risk) may be leveraged to test new innovative solutions by developing proofs of concept, prototypes, and pilots. Innovative mechanisms such as setting up a sovereign tech fund or using blended finance instruments could also be considered to finance resilient DPI. Overall, financing models for DPI, especially for different stages of its lifecycle, is an area that requires more research and experimentation.

The DPI vision of enabling speedy and sustainable service delivery at scale brings with it many changes in the relationship between citizens and states. While entirely essential and inevitable, the true potential of digital infrastructure lies in looking beyond the tech itself to focus on how it interacts with users as individuals, as collectives, and in societies. Approaches like the ODE framework are helpful to bring nuance to ongoing debates as countries begin to make critical choices on both tech and non-tech layers so that DPI can be deployed to meaningfully work towards society’s wellbeing.

This was originally published as part of ORF’s ‘Digital Frontiers’ compendium on 26th October 2022.